Wednesday, December 12, 2018

GCE Terraform notes

Getting started: https://cloud.google.com/community/tutorials/managing-gcp-projects-with-terraform

Wednesday, December 5, 2018

Make yourself work when you just don't want to..

Reason #1 You are putting something off because you are afraid you will screw it up.

Solution: Adopt a “prevention focus.”

There are two ways to look at any task. You can do something because you see it as a way to end up better off than you are now – as an achievement or accomplishment. As in, if I complete this project successfully I will impress my boss,or if I work out regularly I will look amazing. Psychologists call this a promotion focus – and research shows that when you have one, you are motivated by the thought of making gains, and work best when you feel eager and optimistic. Sounds good, doesn’t it? Well, if you are afraid you will screw up on the task in question, this is not the focus for you. Anxiety and doubt undermine promotion motivation, leaving you less likely to take any action at all.

What you need is a way of looking at what you need to do that isn’t undermined by doubt – ideally, one that thrives on it. When you have a prevention focus, instead of thinking about how you can end up better off, you see the task as a way to hang on to what you’ve already got – to avoid loss. For the prevention-focused, successfully completing a project is a way to keep your boss from being angry or thinking less of you. Working out regularly is a way to not “let yourself go.” Decades of research, which I describe in my book Focus, shows that prevention motivation is actually enhanced by anxiety about what might go wrong. When you are focused on avoiding loss, it becomes clear that the only way to get out of danger is to take immediate action. The more worried you are, the faster you are out of the gate.

I know this doesn’t sound like a barrel of laughs, particularly if you are usually more the promotion-minded type, but there is probably no better way to get over your anxiety about screwing up than to give some serious thought to all the dire consequences of doing nothing at all. Go on, scare the pants off yourself. It feels awful, but it works.

Reason #2 You are putting something off because you don’t “feel” like doing it.

Solution: Make like Spock and ignore your feelings. They’re getting in your way.

In his excellent book The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking, Oliver Burkeman points out that much of the time, when we say things like “I just can’t get out of bed early in the morning, ” or “I just can’t get myself to exercise,” what we really mean is that we can’t get ourselves to feellike doing these things. After all, no one is tying you to your bed every morning. Intimidating bouncers aren’t blocking the entrance to your gym. Physically, nothing is stopping you – you just don’t feel like it. But as Burkeman asks, “Who says you need to wait until you ‘feel like’ doing something in order to start doing it?”

Think about that for a minute, because it’s really important. Somewhere along the way, we’ve all bought into the idea – without consciously realizing it – that to be motivated and effective we need to feel like we want to take action. We need to be eager to do so. I really don’t know why we believe this, because it is 100% nonsense. Yes, on some level you need to be committed to what you are doing – you need to want to see the project finished, or get healthier, or get an earlier start to your day. But you don’t need to feel like doing it.

In fact, as Burkeman points out, many of the most prolific artists, writers, and innovators have become so in part because of their reliance on work routines that forced them to put in a certain number of hours a day, no matter how uninspired (or, in many instances, hungover) they might have felt. Burkeman reminds us of renowned artist Chuck Close’s observation that “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

So if you are sitting there, putting something off because you don’t feel like it, remember that you don’t actually need to feel like it. There is nothing stopping you.

Reason #3 You are putting something off because it’s hard, boring, or otherwise unpleasant.

Solution: Use if-then planning.

Too often, we try to solve this particular problem with sheer will: Next time, I will make myself start working on this sooner. Of course, if we actually had the willpower to do that, we would never put it off in the first place. Studies show that people routinely overestimate their capacity for self-control, and rely on it too often to keep them out of hot water.

Do yourself a favor, and embrace the fact that your willpower is limited, and that it may not always be up to the challenge of getting you to do things you find difficult, tedious, or otherwise awful. Instead, use if-then planning to get the job done.

Making an if-then plan is more than just deciding what specific steps you need to take to complete a project – it’s also deciding where and when you will take them.

If it is 2pm, then I will stop what I’m doing and start work on the report Bob asked for.

If my boss doesn’t mention my request for a raise at our meeting, then I will bring it up again before the meeting ends.

By deciding in advance exactly what you’re going to do, and when and where you’re going to do it, there’s no deliberating when the time comes. No do I really have to do this now?, or can this wait till later? or maybe I should do something else instead. It’s when we deliberate that willpower becomes necessary to make the tough choice. But if-then plans dramatically reduce the demands placed on your willpower, by ensuring that you’ve made the rightdecision way ahead of the critical moment.

Thursday, October 18, 2018

Help Your Team Do More Without Burning Out

Source

As we begin our coaching session, Nick is fired up. He radiates energy, his eyes are beaming with determination, and he never really comes to a full rest. He speaks passionately of a new initiative he is spearheading, taking on the looming threats from Silicon Valley, and rethinking his company’s business model completely.

I recognize this behavior in Nick, having seen it many times over the years since he was first singled out as a high-potential talent. “Restless and relentless” have been his trademarks as he has risen through the ranks and aced one challenge after another.

But this time, I notice something new. Beneath the usual can-do attitude there is an inkling of something else: Mild disorientation and even signs of exhaustion. “It’s like sprinting all you can, and then you turn a corner and find that you are actually setting out on a marathon,” he remarks at one point. And as we speak, this sneaking feeling of not keeping pace turns out to be Nick’s true concern: Is he about to lose his magic touch and burn out?

Nick is not alone.

In a psychologist’s practice, common themes rise and wane across a cohort of clients. Right now, I see a surge of concern about speed: getting ahead and staying ahead. More clients use similar metaphors about “running to stand still” or feeling “caught on a track.” Invariably, their first response is to speed up and run faster.

But the impulse to simply run faster to escape friction is obviously of no use for the long haul of a life-long career. In fact, our immediate behavioral response to friction shares one feature with much of the general advice about speeding up: It is plainly counterproductive and leads to burn out rather than break out.

To add insult to injury, the way to wrestle effectively with the challenge of sustainable speed is somewhat counterintuitive and even disconcerting — especially to high-performing leaders who have successfully relied on their personal drive to make results.

Rather than running faster, Nick needs to make different moves altogether. First, he must let go of his obsession with his own development, his own needs, his own performance, and his own pace. Second, he must start obsessing about other people.

It may seem illogical, but the leap to a new growth curve begins by realizing that the recipe is not to take on more and speed up, but to slow down and let go of some of the issues that have been your driving forces: power, prestige, responsibility, recognition, or face-time.

The talent phase in our careers tends to be profoundly self-centered, even narcissistic. If you need to move on from the first growth curve in your career, and want to take on more challenges, you need to exchange ego-drive for co-drive.

Co-drive requires that you momentarily forget yourself — and instead focus on others. The shift involves an understanding that you have already proven yourself. At this stage, the point is to help those around you perform. The change to co-drive involves moving from a stage of grabbing territory to a stage characterized by letting go of command and control.

Be energizing, not energetic. Here is the paradox: You can actually speed things up by slowing down. There is no doubt that being energetic is contagious and therefore a short-term source of momentum. But if you lead by example all the time, your batteries will eventually run dry. You risk being drained at the vey point when your leadership is needed the most. Conveying a sense of urgency is useful, but an excess of urgency suffocates team development and reflection at the very point it is needed. “Code red” should be left for real emergencies.

Nick has always had a weak point for people, who, like himself, are high-energy and get things done. These “Energizer Bunnies” are his star players. However, with the co-drive mindset, Nick needs to widen his sights and recognize and reward people who are good at energizing others. Energizing behavior is unselfish, generous, and praises, not just progress, but personality too.

Seek self-propulsion, not pace-setting. If you lead by beating the drum, setting tight deadlines, and burning the midnight oil, your team becomes overly dependent on your presence. Sustainable speed is achievable only if the team propels itself without your presence. Jim Collins wrote that great leaders don’t waste time telling time, they build clocks.

Self-propulsion comes from letting go of control, resisting the urge to make detailed corrections and allowing for informal leadership to flourish. As Ron Heifetz advocates, true leadership is realizing that you need to “give the work back” instead of being the hero who sweeps in and solves everybody’s problems.

In Nick’s case, he should resist the urge to take the driver’s seat and allow himself to take the passenger seat instead. Leading from the side-line, not the front line will change his perspective. Instead of looking at the road and navigating traffic, he is able to monitor how the driver is actually doing and what needs to improve. In his mind, he should fire himself — momentarily — and see what happens to his team when he sets them free and asks them to take charge instead of looking to him for answers, deadlines and decisions.

Congregate, don’t delegate. From very early on in our careers we learn that in order to solve big, complex issues fast, we must decompose the problem into smaller parts and delegate these pieces to specialists to get leverage. Surely, you can make good music by patching together the tracks of individual recordings. But true masterpieces come alive when the orchestra plays together.

One example is the so-called Trauma Center approach. When a trauma patient comes in, all specialists are in the room assessing the patient at the same time, but constantly allowing the most skilled specialist to take the lead (and talk), not the designated leader.

The most well-run trauma teams I have observed know when to jump in and when to step back. To put it simply, it’s no use working on a finger if the heart is failing. A trauma team relies on trust and patience. They trust each other’s specialty and work very symmetrically. There is a very strong “no one leaves before we are done” mentality in those teams.

To Nick, this may sound like good old teamwork, and while Nick is certainly driven by a good measure of self-interest, he is also an accomplished leader who masters the dynamics of teamwork: Having shared goals, assigning roles and responsibilities, and investing in the team.

But there is more to co-drive than plain teamwork. It is about re-working the collaborative process it self. Rather than cubicled problem-solving, sustainable speed requires a shift toward more collective creation: Gathering often, engaging issues openly and inviting others to improve on your own thoughts and decisions.

Co-drive requires a different mindset. And it goes beyond team-work. Adam Grant from Wharton has done research demonstrating that a generous and giving attitude towards others enhances team performance.

Try, for instance, to take a look at your own behavior yesterday and gauge the balance between giving and taking. Givers offer assistance, share knowledge, and focus on introducing and helping others. Takers attempt to get other people to do something that will ultimately benefit them, while they act as gatekeepers of their own knowledge.

Grant’s conclusion is clear: a willingness to help others is not just

the essence of effective cooperation and innovation — it is also the

key to accelerating your own performance.

The developmental psychologist Robert Kegan calls the leap a subject/object shift. You progress from seeing and navigating in the world on the basis of your own needs and motives — and allowing yourself to be governed by these needs — to seeing yourself from an external position as a part of an organism.

It requires a certain caliber and self-assuredness to act in this way. The ability to put your ego on hold may require a great effort. It might be worthwhile reminding yourself of the words of the American President Harry Truman: “It is incredible what you can achieve, if you don’t care who gets the credit.” If you succeed in making this shift, and thereby improving the skills of the people around you, then you will also experience a greater degree of freedom.

So next time you are feeling stuck, don’t ask: “How can I push harder?” but “Where can I let go?”

As we begin our coaching session, Nick is fired up. He radiates energy, his eyes are beaming with determination, and he never really comes to a full rest. He speaks passionately of a new initiative he is spearheading, taking on the looming threats from Silicon Valley, and rethinking his company’s business model completely.

I recognize this behavior in Nick, having seen it many times over the years since he was first singled out as a high-potential talent. “Restless and relentless” have been his trademarks as he has risen through the ranks and aced one challenge after another.

But this time, I notice something new. Beneath the usual can-do attitude there is an inkling of something else: Mild disorientation and even signs of exhaustion. “It’s like sprinting all you can, and then you turn a corner and find that you are actually setting out on a marathon,” he remarks at one point. And as we speak, this sneaking feeling of not keeping pace turns out to be Nick’s true concern: Is he about to lose his magic touch and burn out?

Nick is not alone.

In a psychologist’s practice, common themes rise and wane across a cohort of clients. Right now, I see a surge of concern about speed: getting ahead and staying ahead. More clients use similar metaphors about “running to stand still” or feeling “caught on a track.” Invariably, their first response is to speed up and run faster.

But the impulse to simply run faster to escape friction is obviously of no use for the long haul of a life-long career. In fact, our immediate behavioral response to friction shares one feature with much of the general advice about speeding up: It is plainly counterproductive and leads to burn out rather than break out.

To add insult to injury, the way to wrestle effectively with the challenge of sustainable speed is somewhat counterintuitive and even disconcerting — especially to high-performing leaders who have successfully relied on their personal drive to make results.

From ego-drive to co-drive

The key to speeding up without burning up is a concept I call co-drive. Sustainable speed does not come from ego-drive, that is, your own personal performance or energy level, but rather from a different approach to engaging with people around you.Rather than running faster, Nick needs to make different moves altogether. First, he must let go of his obsession with his own development, his own needs, his own performance, and his own pace. Second, he must start obsessing about other people.

It may seem illogical, but the leap to a new growth curve begins by realizing that the recipe is not to take on more and speed up, but to slow down and let go of some of the issues that have been your driving forces: power, prestige, responsibility, recognition, or face-time.

The talent phase in our careers tends to be profoundly self-centered, even narcissistic. If you need to move on from the first growth curve in your career, and want to take on more challenges, you need to exchange ego-drive for co-drive.

Co-drive requires that you momentarily forget yourself — and instead focus on others. The shift involves an understanding that you have already proven yourself. At this stage, the point is to help those around you perform. The change to co-drive involves moving from a stage of grabbing territory to a stage characterized by letting go of command and control.

Beyond teamwork

So here is what Nick needs to do: Rather than striving to be energetic, he should aim to be energizing. Rather than setting the pace, he should aspire to make teams self-propelling. Instead of delegating tasks, he should learn to lead by congregating.Be energizing, not energetic. Here is the paradox: You can actually speed things up by slowing down. There is no doubt that being energetic is contagious and therefore a short-term source of momentum. But if you lead by example all the time, your batteries will eventually run dry. You risk being drained at the vey point when your leadership is needed the most. Conveying a sense of urgency is useful, but an excess of urgency suffocates team development and reflection at the very point it is needed. “Code red” should be left for real emergencies.

Nick has always had a weak point for people, who, like himself, are high-energy and get things done. These “Energizer Bunnies” are his star players. However, with the co-drive mindset, Nick needs to widen his sights and recognize and reward people who are good at energizing others. Energizing behavior is unselfish, generous, and praises, not just progress, but personality too.

Seek self-propulsion, not pace-setting. If you lead by beating the drum, setting tight deadlines, and burning the midnight oil, your team becomes overly dependent on your presence. Sustainable speed is achievable only if the team propels itself without your presence. Jim Collins wrote that great leaders don’t waste time telling time, they build clocks.

Self-propulsion comes from letting go of control, resisting the urge to make detailed corrections and allowing for informal leadership to flourish. As Ron Heifetz advocates, true leadership is realizing that you need to “give the work back” instead of being the hero who sweeps in and solves everybody’s problems.

In Nick’s case, he should resist the urge to take the driver’s seat and allow himself to take the passenger seat instead. Leading from the side-line, not the front line will change his perspective. Instead of looking at the road and navigating traffic, he is able to monitor how the driver is actually doing and what needs to improve. In his mind, he should fire himself — momentarily — and see what happens to his team when he sets them free and asks them to take charge instead of looking to him for answers, deadlines and decisions.

Congregate, don’t delegate. From very early on in our careers we learn that in order to solve big, complex issues fast, we must decompose the problem into smaller parts and delegate these pieces to specialists to get leverage. Surely, you can make good music by patching together the tracks of individual recordings. But true masterpieces come alive when the orchestra plays together.

One example is the so-called Trauma Center approach. When a trauma patient comes in, all specialists are in the room assessing the patient at the same time, but constantly allowing the most skilled specialist to take the lead (and talk), not the designated leader.

The most well-run trauma teams I have observed know when to jump in and when to step back. To put it simply, it’s no use working on a finger if the heart is failing. A trauma team relies on trust and patience. They trust each other’s specialty and work very symmetrically. There is a very strong “no one leaves before we are done” mentality in those teams.

To Nick, this may sound like good old teamwork, and while Nick is certainly driven by a good measure of self-interest, he is also an accomplished leader who masters the dynamics of teamwork: Having shared goals, assigning roles and responsibilities, and investing in the team.

But there is more to co-drive than plain teamwork. It is about re-working the collaborative process it self. Rather than cubicled problem-solving, sustainable speed requires a shift toward more collective creation: Gathering often, engaging issues openly and inviting others to improve on your own thoughts and decisions.

Co-drive requires a different mindset. And it goes beyond team-work. Adam Grant from Wharton has done research demonstrating that a generous and giving attitude towards others enhances team performance.

Try, for instance, to take a look at your own behavior yesterday and gauge the balance between giving and taking. Givers offer assistance, share knowledge, and focus on introducing and helping others. Takers attempt to get other people to do something that will ultimately benefit them, while they act as gatekeepers of their own knowledge.

Maturity and Caliber

Headhunters call this change of perspective from ego-drive to co-drive “executive maturity.” The mature leader’s burning question is: how do I help others perform?The developmental psychologist Robert Kegan calls the leap a subject/object shift. You progress from seeing and navigating in the world on the basis of your own needs and motives — and allowing yourself to be governed by these needs — to seeing yourself from an external position as a part of an organism.

It requires a certain caliber and self-assuredness to act in this way. The ability to put your ego on hold may require a great effort. It might be worthwhile reminding yourself of the words of the American President Harry Truman: “It is incredible what you can achieve, if you don’t care who gets the credit.” If you succeed in making this shift, and thereby improving the skills of the people around you, then you will also experience a greater degree of freedom.

So next time you are feeling stuck, don’t ask: “How can I push harder?” but “Where can I let go?”

Wednesday, October 3, 2018

Closer to emacs as a window manager

Multi-term - finally (probably for a while) has support for remapping important keys.

auto-dim-other - very useful as it dims other buffers making it easier to know which is the active buffer

windmove - built in since emacs 21, allows binding keys to 'windmove-[left|right|up|down]. Decided that C-cC-n, C-cC-p, C-cC-a, C-cC-f are the easiest for moving around the buffers and the most similar to current functionality (C-n moves down a line, C-p moves up a line, C-a moves to the front of a line, C-e to the end). This does mean unbinding these keys from all the various modes that want to use these keys as well, the biggest pain being elpy-flymake, which doesn't seem to want to honor hooks attached to elpy-flymake-mode-hook or elpy-mode-hook.

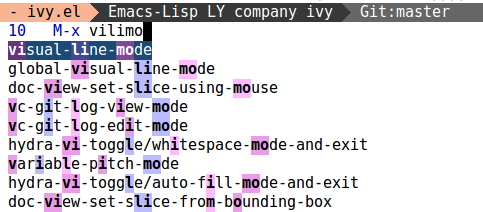

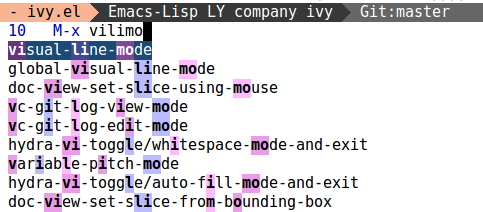

ivy - much nicer matching and drop-down menus for things such as M-x functions

counsel - provides lots of symbol completion for various modes and in particular, ivy.

codesearch - tool for using google codesearch

counsel-codesearch - counsel bindings for codesearch

find-file-in-repo - a faster code search tool using the indexing provided by git (or other dvcs).

auto-dim-other - very useful as it dims other buffers making it easier to know which is the active buffer

windmove - built in since emacs 21, allows binding keys to 'windmove-[left|right|up|down]. Decided that C-cC-n, C-cC-p, C-cC-a, C-cC-f are the easiest for moving around the buffers and the most similar to current functionality (C-n moves down a line, C-p moves up a line, C-a moves to the front of a line, C-e to the end). This does mean unbinding these keys from all the various modes that want to use these keys as well, the biggest pain being elpy-flymake, which doesn't seem to want to honor hooks attached to elpy-flymake-mode-hook or elpy-mode-hook.

ivy - much nicer matching and drop-down menus for things such as M-x functions

counsel - provides lots of symbol completion for various modes and in particular, ivy.

codesearch - tool for using google codesearch

counsel-codesearch - counsel bindings for codesearch

find-file-in-repo - a faster code search tool using the indexing provided by git (or other dvcs).

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Building Emacs

source

Enable 'Source code' in 'Ubuntu Software' in

install build tools

Enable 'Source code' in 'Ubuntu Software' in

/usr/bin/python3 /usr/bin/software-properties-gtk

install build tools

sudo apt install build-essential checkinstallbuild emacs dependencies

sudo apt-get build-dep emacs24clone emacs git repo

git clone -b master git://git.sv.gnu.org/emacs.gitcreate and run config script

./autogen.sh && ./configuremake and make install

make && sudo make install

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

Predictions for new job

Started a new job recently. Going to make some predictions and try to keep track of how things go. I've meant to do this with past jobs, but got too complacent. These predictions are made after a month at the job.

The company has enough money for at least two years of development, but is already actively perusing very big contracts early in the development cycle, requiring engineers to put in exceptional amounts of work/hours in order to meet promises. They should have taken the time to produce a reasonably stable quality project before pursuing such high value targets.

CEO I was warned before hand that they were either a fraud (due to fraudulent behavior in the past in discussing with previous coworkers), or a bungling fool. They're proving to be a fool. Sells features that aren't implemented, pushes the team hard to work exceptional hours to meet those promises.

COO good personality, but not doing their assigned job and not turning the environment from a fraternatory (frat-house drug lab) into an actual professional laboratory. Should vacate the position to be filled by someone with the intent on fulfilling the duties of the position and take another position more in line with what they want to achieve within the company.

Both CEO and COO have exhibited outright cowardice in certain situations, which could indicate that they will not stand up for the company and instead denigrate the engineering team in order to attempt to save face/appease upset customers as to issues encountered with missing features or bugs. Both are clearly taking advantage of a significant portion of the extremely young work force (two key employees are 20 years old) with ego manipulation and appealing to their delusions of grandeur in lieu of a reasonable salary.

CTO exceptionally good in the field in question as well as software development. Has developed very high quality code and made very large improvements to the overall working of the system, but unable to handle criticism or comments. Has repeatedly behaved exceptionally unprofessionally (out right childishly) in response to derision of how they feel testing should be done, released code and manhandled temporary configurations in detrimental ways moments before a production system was to go live, and threw out right fits when the same level of pedantry was applied to their PR's as they apply to their employee PR's (such as pep8'ing other engineers code).

Overall the engineering team is exceptional, producing incredible amounts of very good code and remarkable improvements to the product. Will the draw backs of the C-levels outweigh the quality of the dev team and the early-to-market advantage they have over other similar companies? Hopefully I'll be around long enough to find out personally.

The company has enough money for at least two years of development, but is already actively perusing very big contracts early in the development cycle, requiring engineers to put in exceptional amounts of work/hours in order to meet promises. They should have taken the time to produce a reasonably stable quality project before pursuing such high value targets.

CEO I was warned before hand that they were either a fraud (due to fraudulent behavior in the past in discussing with previous coworkers), or a bungling fool. They're proving to be a fool. Sells features that aren't implemented, pushes the team hard to work exceptional hours to meet those promises.

COO good personality, but not doing their assigned job and not turning the environment from a fraternatory (frat-house drug lab) into an actual professional laboratory. Should vacate the position to be filled by someone with the intent on fulfilling the duties of the position and take another position more in line with what they want to achieve within the company.

Both CEO and COO have exhibited outright cowardice in certain situations, which could indicate that they will not stand up for the company and instead denigrate the engineering team in order to attempt to save face/appease upset customers as to issues encountered with missing features or bugs. Both are clearly taking advantage of a significant portion of the extremely young work force (two key employees are 20 years old) with ego manipulation and appealing to their delusions of grandeur in lieu of a reasonable salary.

CTO exceptionally good in the field in question as well as software development. Has developed very high quality code and made very large improvements to the overall working of the system, but unable to handle criticism or comments. Has repeatedly behaved exceptionally unprofessionally (out right childishly) in response to derision of how they feel testing should be done, released code and manhandled temporary configurations in detrimental ways moments before a production system was to go live, and threw out right fits when the same level of pedantry was applied to their PR's as they apply to their employee PR's (such as pep8'ing other engineers code).

Overall the engineering team is exceptional, producing incredible amounts of very good code and remarkable improvements to the product. Will the draw backs of the C-levels outweigh the quality of the dev team and the early-to-market advantage they have over other similar companies? Hopefully I'll be around long enough to find out personally.

Friday, July 20, 2018

Better fuzzy matching in emacs

source

Step 2: configure

Step 3: optionally configure

Recently, I wrote some code to add better highlighting for Ivy's fuzzy matcher. Here's a quick step-by-step to get an equivalent of flx-ido-mode working with Ivy.

Step 1: install the packages

M-x

package-install - counsel and flx (MELPA should be configured).

Step 2: configure ivy-re-builders-alist

Here's the default setting:

(setq ivy-re-builders-alist

'((t . ivy--regex-plus)))

The default matcher will use a

.* regex wild card in place of each single space in the input. If you want to use the fuzzy matcher, which instead uses a .* regex wild card between each input letter, write this in your config:(setq ivy-re-builders-alist

'((t . ivy--regex-fuzzy)))

You can also mix the two regex builders, for example:

(setq ivy-re-builders-alist

'((ivy-switch-buffer . ivy--regex-plus)

(t . ivy--regex-fuzzy)))

The

t key is used for all fall-through cases, otherwise the key is the command or collection name.

The fuzzy matcher often results in substantially more matching candidates than the regular one for similar input. That's why some kind of sorting is important to bring the more relevant matching candidates to the start of the list. Luckily, that's already been figured out in

flx, so to have it working just make sure that the flx package is installed.

Step 3: optionally configure ivy-initial-inputs-alist

The

ivy-initial-inputs-alist variable is pretty useful in conjunction with the default matcher. It's usually used to insert ^ into the input area for certain commands.

If you're going fuzzy all the way, you can do without the initial

^, and simply let flx (hopefully) sort the matches in a nice way:(setq ivy-initial-inputs-alist nil)

The result

Here's how M-x

counsel-M-x looks like now:

Monday, July 16, 2018

Exercise in futility: evdev

Each new install of linux entails revising customizations in day long attempts to get the new environment working as it was in a previous incarnation.

Simply copying the evdev.mouseless files did not work as they caused an archaic

"Error loading new keyboard description"

each time a custom keybinding option was called such as

"setxkbmap -option windows_ctrl:ctrl_fkey"

After a nightmare multi-hour run around, trying to move files around, taking directives out, replacing symlinks with actual files, it all just started working again. One un tested culprit could have been the cache in /var/lib/xkb/, which was empty when the code started working again.

Simply copying the evdev.mouseless files did not work as they caused an archaic

"Error loading new keyboard description"

each time a custom keybinding option was called such as

"setxkbmap -option windows_ctrl:ctrl_fkey"

After a nightmare multi-hour run around, trying to move files around, taking directives out, replacing symlinks with actual files, it all just started working again. One un tested culprit could have been the cache in /var/lib/xkb/, which was empty when the code started working again.

Sunday, February 25, 2018

rrd data in postgres?

source

With the latest advances in PostgreSQL (and other db’s), a relational

database begins to look like a very viable TS storage platform. In

this write up I attempt to show how to store TS in PostgreSQL. (2016-12-17 Update:

there is a part 2 of this article.)

A TS is a series of [timestamp, measurement] pairs, where measurement is typically a floating point number. These pairs (aka “data points”) usually arrive at a high and steady rate. As time goes on, detailed data usually becomes less interesting and is often consolidated into larger time intervals until ultimately it is expired.

One problem with this is the inefficiency of appending data. An insert requires a look up of the new id, locking and (usually) blocks until the data is synced to disk. Given the TS’s “firehose” nature, the database can quite quickly get overwhelmed.

This approach also does not address consolidation and eventual expiration of older data points.

A everyday life example of an RRD is a week. Imagine a structure of 7 slots, one for each day of the week. If you know today’s date and day of the week, you can easily infer the date for each slot. For example if today is Tuesday, April 1, 2008, then the Monday slot refers to March 31st, Sunday to March 30th and (most notably) Wednesday to March 26.

Here’s what a 7-day RRD of average temperature might look as of Tuesday, April 1:

RRD’s are also very space-efficient. In the above example we specified the date of every slot for clarity. In an actual implementation only the date of the last slot needs to be stored, thus the RRD can be kept as a sequence of 7 numbers plus the position of the last entry and it’s timestamp. In Python syntax it’d look like this:

This is where using PostgrSQL arrays become very useful.

We could populate the whole RRD in a single statement:

Having the series split into chunks also paves the way for some kind of a caching layer, we could have a server which waits for one row worth of data points to accumulate, then flushes then all at once.

For simplicity, let’s take the above example and expand the RRD to 4 weeks, while keeping 1 week per row. In our table definition we need provide a way for keeping the order of every row of the TS with a column named n, and while we’re at it, we might as well introduce a notion of an id, so as to be able to store multiple TS in the same table.

Let’s start with two tables, one called rrd where we would store the last position and date, and another called ts which would store the actual data.

This article omits a lot of detail such as having resolution finer than one day, but it does describe the general idea. For an actual implementation of this you might want to check out a project I’ve been working on: tgres

A TS is a series of [timestamp, measurement] pairs, where measurement is typically a floating point number. These pairs (aka “data points”) usually arrive at a high and steady rate. As time goes on, detailed data usually becomes less interesting and is often consolidated into larger time intervals until ultimately it is expired.

The obvious approach

The “naive” approach is a three-column table, like so:1

| |

One problem with this is the inefficiency of appending data. An insert requires a look up of the new id, locking and (usually) blocks until the data is synced to disk. Given the TS’s “firehose” nature, the database can quite quickly get overwhelmed.

This approach also does not address consolidation and eventual expiration of older data points.

Round-robin database

A better alternative is something called a round-robin database. An RRD is a circular structure with a separately stored pointer denoting the last element and its timestamp.A everyday life example of an RRD is a week. Imagine a structure of 7 slots, one for each day of the week. If you know today’s date and day of the week, you can easily infer the date for each slot. For example if today is Tuesday, April 1, 2008, then the Monday slot refers to March 31st, Sunday to March 30th and (most notably) Wednesday to March 26.

Here’s what a 7-day RRD of average temperature might look as of Tuesday, April 1:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

RRD’s are also very space-efficient. In the above example we specified the date of every slot for clarity. In an actual implementation only the date of the last slot needs to be stored, thus the RRD can be kept as a sequence of 7 numbers plus the position of the last entry and it’s timestamp. In Python syntax it’d look like this:

1

| |

Round-robin in PostgreSQL

Here is a naive approach to having a round-robin table. Carrying on with our 7 day RRD example, it might look like this:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1

| |

This is where using PostgrSQL arrays become very useful.

Using PostgreSQL arrays

An array would allow us to store the whole series in a single row. Sticking with the 7-day RRD example, our table would be created as follows:1 2 3 | |

We could populate the whole RRD in a single statement:

1

| |

1

| |

But it could be even more efficient

Under the hood, PostgreSQL data is stored in pages of 8K. It would make sense to keep chunks in which our RRD is written to disk in line with page size, or at least smaller than one page. (PostgreSQL provides configuration parameters for how much of a page is used, etc, but this is way beyond the scope of this article).Having the series split into chunks also paves the way for some kind of a caching layer, we could have a server which waits for one row worth of data points to accumulate, then flushes then all at once.

For simplicity, let’s take the above example and expand the RRD to 4 weeks, while keeping 1 week per row. In our table definition we need provide a way for keeping the order of every row of the TS with a column named n, and while we’re at it, we might as well introduce a notion of an id, so as to be able to store multiple TS in the same table.

Let’s start with two tables, one called rrd where we would store the last position and date, and another called ts which would store the actual data.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 | |

This article omits a lot of detail such as having resolution finer than one day, but it does describe the general idea. For an actual implementation of this you might want to check out a project I’ve been working on: tgres

Innovation engine

source

Practically every company innovates. But few do so in an orderly, reliable way. In far too many organizations, the big breakthroughs happen despite the company. Successful innovations typically follow invisible development paths and require acts of individual heroism or a heavy dose of serendipity. Successive efforts to jump-start innovation through, say, hack-a-thons, cash prizes for inventive concepts, and on-again, off-again task forces frequently prove fruitless. Great ideas remain captive in the heads of employees, innovation initiatives take way too long, and the ideas that are developed are not necessarily the best efforts or the best fit with strategic priorities.

Most executives will freely admit that their innovation engine doesn’t hum the way they would like it to. But turning sundry innovation efforts into a function that operates consistently and at scale feels like a monumental task. And in many cases it is, requiring new organizational structures, new hires, and substantial investment, as the “innovation factory” Procter & Gamble built in the early 2000s did.

We borrow the language for this term from the world of lean start-ups, where “minimum viable product” denotes a stripped-down functional prototype used as a starting point for developing a new offering. “Minimum viable innovation system” refers to the essential building blocks that allow a company to begin creating a reliable, strategically focused innovation function. An MVIS will ensure that good ideas are encouraged, identified, shared, reviewed, prioritized, resourced, developed, rewarded, and celebrated. But it will not require years of work, fundamental changes to the way the organization runs, or a significant reallocation of resources.

What it will require is senior management attention—most critically from some member of the top leadership team. That might be the chief executive officer or a chief innovation officer, but it doesn’t have to be. If you’re responsible for innovation in your company at the highest level, we’re talking to you. With a little help from other executives and innovation practitioners, you can set up an MVIS by completing four basic steps in no more than 90 days, with limited investment and without hiring anyone extra. And as early success builds confidence in your innovation capabilities, it will set the stage for further progress.

The MVIS encompasses both types of innovation, but it’s critical that everyone involved in an MVIS (or any innovation program) understand the difference between the two buckets. The failure to do so causes many companies to either discount the importance of innovations that strengthen the ongoing business or to demand too much revenue from the new-growth initiatives too early. Agreeing on what to call the two buckets is a good starting place. For the purposes of this discussion we’ll call the first one “core innovations” and the second “new-growth innovations.”

Innovation projects meant to strengthen the core should be tied to the current strategy and managed mostly within the main business’s organizational structure. (The MVIS will keep track of them, though, as you’ll see later on.) They’re the projects expected to offer rapid and substantial returns in the near future and need to be funded at scale.

Conceivably, all your current innovation projects may be core. But what of the future? Will they be enough to enable you to reach your longer-term financial targets? If your company is typical, the answer is no. There will be a gap between your growth goals and what your current operations and core innovations can generate. It’s the purpose of the new-growth innovations to fill that gap.

New-growth initiatives push the frontier of your strategy by offering new or complementary products to existing customers, moving into adjacent product or geographic markets, or developing something utterly original, perhaps delivered in a completely novel way. The larger your company’s growth gap, the further from your core those innovation efforts will likely need to be, and the longer it will take to realize substantial revenue from them.

You can work up a serviceable estimate of the size of the gap if you spend up to two weeks developing rough but honest numbers for the revenue and profits your current operations will deliver in the next five years and then compare them with your five-year goals. This will give you a basic sense of what percentage of your time, effort, and resources needs to be focused on core innovation, and what percentage on new-growth efforts, and how ambitious the latter need to be.

When your growth gap is fairly large, you may wish to subdivide your new-growth efforts so that you can map them to different possible directions for future growth. This being a minimum innovation effort, we suggest designating no more than three such categories.

Manila Water is a public/private partnership in the Philippines that

has done a good job of mapping its core and new-growth innovation

efforts to its current and future goals. In 1997 it received a

concession to provide water services to the eastern part of the city of

Manila, covering about 6 million people. At the time only about 30% of

the city’s households had reliable access to water. In the next 16 years

the company made it available to almost every home in the area and

approached international levels on key benchmarks such as pressure,

purity, and turbidity.

The organization couldn’t have achieved such impressive performance without being highly innovative in the way it solved the challenges of operating within the chaotic environment of the Philippines. To improve the productivity of the core, it needed to keep pursuing those kinds of innovations—which it dubbed “core optimization.”

However, in 2013, CEO Gerardo Ablaza recognized that core optimization would not be enough to reach Manila Water’s long-term growth goals. The company’s calculations made it clear that over the next few years, 80% of its growth had to come from outside the core.

To fill such a large gap, Ablaza and his leadership team decided that the new-growth initiatives should fall into two broad categories: The first was adjacency moves, in which Manila Water would export its core business model to other geographic markets. The second was the pursuit of new kinds of offerings entirely, beyond the core mission of providing clean water.

That move presented Manila Water with a challenge: The more novel a category of innovation is, the more it will run counter to systems and processes designed to strengthen and support the current business. The next three pieces of the MVIS puzzle help companies overcome that difficulty.

How do you pick them? You could spend months or even years conducting a comprehensive analysis, but of course we don’t recommend that. Instead we suggest doing three weeks of research, with the aid of a handful of executives you expect will eventually be involved in your innovation efforts. Have them meet with at least a dozen customers, probing for unmet needs that could be the foundation of a new-growth innovation, and investigate new developments in and around your industry. Also, take a close look at new-growth efforts currently bubbling up inside your organization. These sometimes signal strategic objectives that aren’t yet getting proper attention from senior management. For example, when one financial services company examined the ideas emerging organically within its ranks, it saw that a number of them involved sophisticated analysis of customer data, even though it hadn’t yet announced that “big data” would be a strategic imperative. Competitive forces and customer demands had naturally begun to attract organizational energy.

Next, lock the members of the senior leadership team in a room for an afternoon, share the findings, and instruct them not to leave until they have identified three strategic opportunity areas that each combine the following:

If you take care to combine all three criteria, you can avoid some of the more common innovation traps, such as pursuing a phantom opportunity only because it seems so big that there must be money in it somewhere, or wandering into a new market where you have no natural advantage. Manila Water had initially considered, for instance, whether it might expand into advertising. After all, every month it was sending out millions of paper bills, on which someone might want to advertise, and the Filipino ad market was growing. But ultimately that area was deemed too far from the company’s existing capabilities to be reasonably defended against more-experienced competitors.

Identifying strategic opportunity areas will direct the energies of

forward-thinking employees who might be playing with ideas at the

fringes of your organization. It also helps highlight where people might

be wasting their time. After all, its corollary is that it defines what

you are not going to do. That’s something we’ll focus on in the next section.

Even a minimum viable innovation system requires that at least one person (and typically more) get up every morning and go to sleep every night thinking about nothing but innovation. (That won’t be you, though it should be someone who reports to you. As the executive sponsor, you presumably have other responsibilities as well.)

But there’s no need to recruit an army. Manila Water created a three-person team to explore the first two strategic areas it identified. The team then developed a backup list of half a dozen extra opportunities that could be pursued if the first set didn’t pan out. We generally recommend starting in this focused way rather than setting up a large innovation function, which often creates work for itself to justify its existence. That said, we do recommend building the capacity to handle at least two ideas at once, since there inevitably will be course corrections and failure.

Finding the bulk of your zombies is a straightforward process: List all the innovation efforts that have the equivalent of at least one half-time employee working on them. Try to identify which market each idea targets. Estimate the size of the opportunity, and inventory the resources currently devoted to it. Which efforts enhance your core strategy and which focus on strategic opportunity areas? It should be fairly easy to identify the projects that are neither and are frittering away your resources.

In 2011, when Francesco Vanni d’Archirafi, then CEO of Citi Transaction Services, pushed his organization to track its innovation efforts, substantial duplication and fruitless efforts came to light. CTS streamlined its innovation portfolio by consolidating 75 mobile projects into 10, which liberated resources and increased strategic focus.

Identifying zombies is easier than killing them off, however. Many people find it hard to throw in the towel on a project that might somehow, someday work. And few people have the fortitude to admit that their project is essentially the same as someone else’s.

As a start, consider instituting “zombie amnesty,” whereby people can admit that their idea is too small, not strategic enough, or too riddled with difficult-to-address risks to justify further funding. Make it clear that there will be no penalty for purging a project. In fact, hold a celebration to honor those who do. They’re heroes and should be treated as such. One round of amnesty will probably release enough resources to get your innovation team up and running, although it’s a good idea to hold the exercise every couple of years to ensure that efforts haven’t wandered off course.

Over the years, innovation thinkers and practitioners have offered up a wealth of best practices aimed at making new-growth innovation as orderly as the processes for manufacturing and marketing mature products. Companies like Intuit, Syngenta, and General Electric have elaborate systems to spread those practices throughout their organizations. In essence these systems combine some formal training with immersion in an actual product-development experience. A simpler version of this is an effective starting point for a neophyte MVIS team.

As experienced innovators, we use process checklists to make sure we

haven’t left out any critical step. Those newer to innovation can do the

same. Have your team devour the literature of best innovation practices

and develop its own checklist, hang it on the wall, and refer to it

frequently. (For some of our favorite books, see the sidebar “An

Innovator’s Bookshelf.”) The team members will develop their skills as

they work through problems, but the checklist will help ensure that they

don’t go off the rails in the meantime.

A nonprofit, the Settlement Music School, used this approach to reach new student populations in inventive ways. Founded in 1908, SMS offered classes in jazz and classical music to 5,000 students—primarily children—weekly in the Philadelphia area. Executive director Helen Eaton hoped to transform SMS’s facilities into a “third place,” like a house of worship (or a neighborhood Starbucks), that could provide adults with a sense of community. After dividing her innovation ideas into core and new growth, she identified four strategic opportunity areas she called “best in class,” “community arts changes lives,” “innovation meets changing needs,” and “smart solutions for sustainability and growth.”

In an initiative so far from SMS’s core, many uncertainties needed to be resolved. How would the school attract students? What type of music should they play? One hook could be a culminating concert where the jam band would perform, but maybe the program should more open-ended, with no big event?

Like seasoned innovators, the team laid out the assumptions underpinning a complete business model, which included how the program would be designed, marketed, and delivered. The idea was that a group of like-minded adults would come together and practice under the tutelage of an expert instructor. The class could continue indefinitely, separated into 10-week sessions; at the end of each session the band would hold a concert in the school’s performance space. As instructor Ed Wise told a local publication, “There’s something good for the soul about strapping on the old Fender and banging out a few Jack Bruce lines.”

Would that work? The members of the team had spent enough time with customers to be confident that Adult Rock Band addressed a real market need, and their back-of-the-envelope analysis showed that the program would break even if an individual branch could attract just eight participants. They set out to test the idea by running a pilot at a single branch and then expanding to two more.

The program did well at two branches but struggled at the third. Rather than walk away from the perceived failure, the school did a careful analysis. It showed that SMS needed to fine-tune the classes to the socioeconomic makeup of its local branches, taking into account each community’s musical traditions, cultural traditions, and social networks. As the school continued to innovate and look into why certain programs took hold in one community and not in another, the MVIS team found it could begin to predict the success rates of new offerings. Its success helped SMS earn a coveted grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts to support further investment in innovative programs.

Begin by forming a group of senior leaders who, from then on, will have the autonomy to make decisions about starting, stopping, or redirecting new-growth innovation projects. Don’t just replicate the current executive committee, however. If you do, it will be too easy for group members to default to their corporate-planning mindset or to let day-to-day business creep into discussions about innovations meant to fulfill long-term goals. Manila Water, for instance, picked four members of its top management team to serve on what it called the New Services Review Committee, which met every few weeks to help teams working on new-growth ideas.

In overseeing projects, this group should copy some standard VC operating procedures:

This is something that Mary Jo Haddad, who was the CEO of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children from 2004 to 2013, understood when she kicked off a major innovation effort there in 2010. Haddad created a shepherding mechanism: an 18-person cross-functional team called the Innovation Working Group, which was armed with $250,000 in funding. The IWG helps innovators understand the needs of users, test prototypes, make adjustments, and then build scale. It also works to identify latent organizational innovation talent by running workshops that gather ideas from staff, patients, families, and the public and gives employees with promising proposals the opportunity to step out of their day jobs for a while to push their ideas forward. Equally important, the IWG runs an annual Innovation Expo, which celebrates innovators who experiment with new ideas, regardless of whether they succeed or fail.

While an MVIS approach avoids the arduous work of rewiring a

company’s systems for performance management, budgeting, and supplier

management, it has a downside: It requires senior leaders to get

involved in those issues on an ad hoc basis. For instance, at one

organization a high-performing employee was in danger of losing a

promotion because the innovative business she was helping build didn’t

cross a revenue threshold set by corporate HR’s advancement policies.

But her responsibilities were at least equal to those of many others who

did qualify for promotion, and there were clear signs that, managed

appropriately, her business could deliver substantial long-term revenue.

Her unit leader stepped in to preempt the HR decision.

You might not want to spend time mired in these types of discussions forever. So at some point you may wish to integrate an MVIS into the broader organization—the subject of the next section.

First, consider hardwiring the components of the MVIS that are working well into more-formal systems. Manila Water created a master plan of innovation efforts, which forecast the pace and scale of its investment activities and their financial impact over a multiyear period. CTS assigned individuals to oversee certain processes and created tracking tools to enable them to regularly monitor the portfolio of innovation projects. Though such efforts can feel like creeping bureaucracy, they’re part of the natural maturation of innovation as an organizational capability.

Second, consider creating specialized functions to carry out parts of the innovation process. A small organization might, for example, assign a single person to act as a “scout,” keeping abreast of market changes. A large one might establish a business development team that looks for opportunities to form partnerships and alliances to amplify new-growth efforts. Or it might form groups to conduct ethnographic market research or develop rapid prototyping techniques.

Finally, work on the MVIS should highlight some of the larger barriers to innovation inside an organization. These often reside within corporate budgeting, incentive, and strategic-planning systems, which, after all, are designed to further today’s business, not create tomorrow’s. Rewiring those systems or establishing robust parallels presents substantial challenges but is critical to scaling up and spreading innovation efforts.

Creating an MVIS won’t miraculously turn you into Pixar or Amazon, but it will help you make tangible progress in increasing the predictability and productivity of critical investments in future growth.

Practically every company innovates. But few do so in an orderly, reliable way. In far too many organizations, the big breakthroughs happen despite the company. Successful innovations typically follow invisible development paths and require acts of individual heroism or a heavy dose of serendipity. Successive efforts to jump-start innovation through, say, hack-a-thons, cash prizes for inventive concepts, and on-again, off-again task forces frequently prove fruitless. Great ideas remain captive in the heads of employees, innovation initiatives take way too long, and the ideas that are developed are not necessarily the best efforts or the best fit with strategic priorities.

Most executives will freely admit that their innovation engine doesn’t hum the way they would like it to. But turning sundry innovation efforts into a function that operates consistently and at scale feels like a monumental task. And in many cases it is, requiring new organizational structures, new hires, and substantial investment, as the “innovation factory” Procter & Gamble built in the early 2000s did.

Building a Minimum Viable Innovation System: The First 90 Days

For the past decade we’ve been helping organizations around the globe strengthen their innovation capabilities, and that work has taught us that there’s an important intermediate option between ad hoc innovation and building an elaborate, large-scale innovation factory: setting up a minimum viable innovation system (MVIS).We borrow the language for this term from the world of lean start-ups, where “minimum viable product” denotes a stripped-down functional prototype used as a starting point for developing a new offering. “Minimum viable innovation system” refers to the essential building blocks that allow a company to begin creating a reliable, strategically focused innovation function. An MVIS will ensure that good ideas are encouraged, identified, shared, reviewed, prioritized, resourced, developed, rewarded, and celebrated. But it will not require years of work, fundamental changes to the way the organization runs, or a significant reallocation of resources.

What it will require is senior management attention—most critically from some member of the top leadership team. That might be the chief executive officer or a chief innovation officer, but it doesn’t have to be. If you’re responsible for innovation in your company at the highest level, we’re talking to you. With a little help from other executives and innovation practitioners, you can set up an MVIS by completing four basic steps in no more than 90 days, with limited investment and without hiring anyone extra. And as early success builds confidence in your innovation capabilities, it will set the stage for further progress.

Day 1 to 30: Define Your Innovation Buckets

There’s no shortage of terms for innovation. Sustaining innovations, incremental innovations, continual improvement programs, organic-growth initiatives. Disruptive innovations, breakthrough innovations, new-growth initiatives, white-space and blue-ocean strategies. But strategically speaking, all innovations fall into one of two buckets. In one are innovations that extend today’s business, either by enhancing existing offerings or by improving internal operations. In the other are innovations that generate new growth by reaching new customer segments or new markets, often through new business models.The MVIS encompasses both types of innovation, but it’s critical that everyone involved in an MVIS (or any innovation program) understand the difference between the two buckets. The failure to do so causes many companies to either discount the importance of innovations that strengthen the ongoing business or to demand too much revenue from the new-growth initiatives too early. Agreeing on what to call the two buckets is a good starting place. For the purposes of this discussion we’ll call the first one “core innovations” and the second “new-growth innovations.”

Innovation projects meant to strengthen the core should be tied to the current strategy and managed mostly within the main business’s organizational structure. (The MVIS will keep track of them, though, as you’ll see later on.) They’re the projects expected to offer rapid and substantial returns in the near future and need to be funded at scale.

Conceivably, all your current innovation projects may be core. But what of the future? Will they be enough to enable you to reach your longer-term financial targets? If your company is typical, the answer is no. There will be a gap between your growth goals and what your current operations and core innovations can generate. It’s the purpose of the new-growth innovations to fill that gap.

New-growth initiatives push the frontier of your strategy by offering new or complementary products to existing customers, moving into adjacent product or geographic markets, or developing something utterly original, perhaps delivered in a completely novel way. The larger your company’s growth gap, the further from your core those innovation efforts will likely need to be, and the longer it will take to realize substantial revenue from them.

You can work up a serviceable estimate of the size of the gap if you spend up to two weeks developing rough but honest numbers for the revenue and profits your current operations will deliver in the next five years and then compare them with your five-year goals. This will give you a basic sense of what percentage of your time, effort, and resources needs to be focused on core innovation, and what percentage on new-growth efforts, and how ambitious the latter need to be.

When your growth gap is fairly large, you may wish to subdivide your new-growth efforts so that you can map them to different possible directions for future growth. This being a minimum innovation effort, we suggest designating no more than three such categories.

The organization couldn’t have achieved such impressive performance without being highly innovative in the way it solved the challenges of operating within the chaotic environment of the Philippines. To improve the productivity of the core, it needed to keep pursuing those kinds of innovations—which it dubbed “core optimization.”

However, in 2013, CEO Gerardo Ablaza recognized that core optimization would not be enough to reach Manila Water’s long-term growth goals. The company’s calculations made it clear that over the next few years, 80% of its growth had to come from outside the core.

To fill such a large gap, Ablaza and his leadership team decided that the new-growth initiatives should fall into two broad categories: The first was adjacency moves, in which Manila Water would export its core business model to other geographic markets. The second was the pursuit of new kinds of offerings entirely, beyond the core mission of providing clean water.

That move presented Manila Water with a challenge: The more novel a category of innovation is, the more it will run counter to systems and processes designed to strengthen and support the current business. The next three pieces of the MVIS puzzle help companies overcome that difficulty.

Day 20 to 50: Zero In on a Few Strategic Opportunity Areas

Sophisticated innovators like Procter & Gamble, W.L. Gore, and Apple have elaborate processes to tie their various types of innovation to their short- and longer-term growth goals. The MVIS also does this, but in a simpler way. It makes efficient use of limited resources and productively channels innovators’ passions by focusing innovation efforts on a small number of strategic opportunity areas. These are areas that fit within your new-growth buckets and seem large enough to take the needed bite out of that growth gap.How do you pick them? You could spend months or even years conducting a comprehensive analysis, but of course we don’t recommend that. Instead we suggest doing three weeks of research, with the aid of a handful of executives you expect will eventually be involved in your innovation efforts. Have them meet with at least a dozen customers, probing for unmet needs that could be the foundation of a new-growth innovation, and investigate new developments in and around your industry. Also, take a close look at new-growth efforts currently bubbling up inside your organization. These sometimes signal strategic objectives that aren’t yet getting proper attention from senior management. For example, when one financial services company examined the ideas emerging organically within its ranks, it saw that a number of them involved sophisticated analysis of customer data, even though it hadn’t yet announced that “big data” would be a strategic imperative. Competitive forces and customer demands had naturally begun to attract organizational energy.

Next, lock the members of the senior leadership team in a room for an afternoon, share the findings, and instruct them not to leave until they have identified three strategic opportunity areas that each combine the following:

- A job that many potential customers need to do that no one is addressing very well.

- Either a technology that will enable customers to do that job much more easily, cheaply, or conveniently, or a change in the economic, regulatory, or social landscape that is greatly intensifying the need for that job.

- Some special capability of your company that competitors can’t easily copy that will give you an advantage in seizing this opportunity.

If you take care to combine all three criteria, you can avoid some of the more common innovation traps, such as pursuing a phantom opportunity only because it seems so big that there must be money in it somewhere, or wandering into a new market where you have no natural advantage. Manila Water had initially considered, for instance, whether it might expand into advertising. After all, every month it was sending out millions of paper bills, on which someone might want to advertise, and the Filipino ad market was growing. But ultimately that area was deemed too far from the company’s existing capabilities to be reasonably defended against more-experienced competitors.

Day 20 to 70: Form a Small, Dedicated Team to Develop the Innovations

Because you’re trying to set up a minimum innovation capability, you may think you could layer it into your existing organization by setting aside some time for everyone to innovate. But consider this: About 75% of venture-capital-backed start-ups fail to return one penny to their investors. Fewer than 50% of start-ups make it to their fourth birthday. These are businesses with dedicated teams whose members are pouring every ounce of their souls into succeeding. What hope does a group of part-timers have to beat the odds?Even a minimum viable innovation system requires that at least one person (and typically more) get up every morning and go to sleep every night thinking about nothing but innovation. (That won’t be you, though it should be someone who reports to you. As the executive sponsor, you presumably have other responsibilities as well.)

But there’s no need to recruit an army. Manila Water created a three-person team to explore the first two strategic areas it identified. The team then developed a backup list of half a dozen extra opportunities that could be pursued if the first set didn’t pan out. We generally recommend starting in this focused way rather than setting up a large innovation function, which often creates work for itself to justify its existence. That said, we do recommend building the capacity to handle at least two ideas at once, since there inevitably will be course corrections and failure.

Are We Following the Best Practices?

As experienced innovators, we use checklists to make sure we

haven’t left out any critical step. These lists contain questions we ask

when considering an investment or advising a new-growth innovation

team. You can use them for the same purposes—or as a starting point for

developing your own checklist.

1. Is innovation development being spearheaded by a small, focused team of people who have relevant experience or are prepared to learn as they go?

2. Has the team spent enough time directly with prospective customers to develop a deep understanding of them?

3. In considering novel ways to serve those customers, did the team review developments in other industries and countries?

4. Can the team clearly define the first customer and a path to reaching others?

5. Is the team’s idea consistent with a strategic opportunity area in which the company has a compelling advantage?

6. Is the idea’s proposed business model described in detail?

7. Does the team have a believable hypothesis about how the offering will make money?

8. Have the team members identified all the things that have to be true for this hypothesis to work?

9. Does the team have a plan for testing all those uncertainties, which tackles the most critical ones first? Does each test have a clear objective, a hypothesis, specific predictions, and a tactical execution plan?

10. Are fixed costs low enough to facilitate course corrections?

11. Has the team demonstrated a bias toward action by rapidly prototyping the idea?

Two obstacles, in our experience, may daunt companies at this stage: a

lack of resources and a lack of people with pertinent experience to

staff the MVIS. Here’s how to overcome them:1. Is innovation development being spearheaded by a small, focused team of people who have relevant experience or are prepared to learn as they go?

2. Has the team spent enough time directly with prospective customers to develop a deep understanding of them?

3. In considering novel ways to serve those customers, did the team review developments in other industries and countries?

4. Can the team clearly define the first customer and a path to reaching others?

5. Is the team’s idea consistent with a strategic opportunity area in which the company has a compelling advantage?

6. Is the idea’s proposed business model described in detail?

7. Does the team have a believable hypothesis about how the offering will make money?

8. Have the team members identified all the things that have to be true for this hypothesis to work?

9. Does the team have a plan for testing all those uncertainties, which tackles the most critical ones first? Does each test have a clear objective, a hypothesis, specific predictions, and a tactical execution plan?

10. Are fixed costs low enough to facilitate course corrections?

11. Has the team demonstrated a bias toward action by rapidly prototyping the idea?

Free up resources.

If you’re encountering the first problem, it’s time to bring your invisible innovation efforts out of the shadows. The odds are high that they include “zombie projects”—walking undead that shuffle along slowly but aren’t headed anywhere. Sometimes companies unwittingly spawn zombies by setting up redundant teams for core initiatives. Sometimes new-growth zombies lurk in an organization’s dark corners in unsanctioned efforts.Finding the bulk of your zombies is a straightforward process: List all the innovation efforts that have the equivalent of at least one half-time employee working on them. Try to identify which market each idea targets. Estimate the size of the opportunity, and inventory the resources currently devoted to it. Which efforts enhance your core strategy and which focus on strategic opportunity areas? It should be fairly easy to identify the projects that are neither and are frittering away your resources.

In 2011, when Francesco Vanni d’Archirafi, then CEO of Citi Transaction Services, pushed his organization to track its innovation efforts, substantial duplication and fruitless efforts came to light. CTS streamlined its innovation portfolio by consolidating 75 mobile projects into 10, which liberated resources and increased strategic focus.

Identifying zombies is easier than killing them off, however. Many people find it hard to throw in the towel on a project that might somehow, someday work. And few people have the fortitude to admit that their project is essentially the same as someone else’s.

As a start, consider instituting “zombie amnesty,” whereby people can admit that their idea is too small, not strategic enough, or too riddled with difficult-to-address risks to justify further funding. Make it clear that there will be no penalty for purging a project. In fact, hold a celebration to honor those who do. They’re heroes and should be treated as such. One round of amnesty will probably release enough resources to get your innovation team up and running, although it’s a good idea to hold the exercise every couple of years to ensure that efforts haven’t wandered off course.

Learn by doing.

If your organization is just starting to focus on innovation, it’s unlikely that anyone you appoint to the team will have much experience with it. And yet we promised that you could get started in 90 days without hiring anyone. How?Over the years, innovation thinkers and practitioners have offered up a wealth of best practices aimed at making new-growth innovation as orderly as the processes for manufacturing and marketing mature products. Companies like Intuit, Syngenta, and General Electric have elaborate systems to spread those practices throughout their organizations. In essence these systems combine some formal training with immersion in an actual product-development experience. A simpler version of this is an effective starting point for a neophyte MVIS team.